Robot Friend to Aid Children with 'Lazy Eye' Treatment

Researchers at the University of Waterloo are developing an innovative solution to help children stick to their treatment for amblyopia, commonly known as 'lazy eye'. The interdisciplinary team is creating a social robot designed to educate and motivate both children and their caregivers throughout the treatment process.

of Waterloo are developing an innovative solution to help children stick to their treatment for amblyopia, commonly known as 'lazy eye'. The interdisciplinary team is creating a social robot designed to educate and motivate both children and their caregivers throughout the treatment process.

Amblyopia is a condition where one eye doesn't see as well as the other, potentially leading to permanent vision loss if left untreated. The standard treatment involves patching the stronger eye for several hours daily, which can be challenging for young patients to maintain.

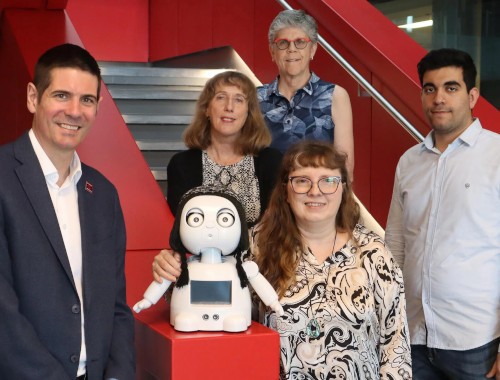

The team's solution involves a social robot named Mirrly, which will interact with families at optometry clinics. Mirrly is designed to engage children by allowing them to place a patch on its eye, fostering a sense of kinship. It will also educate parents by visually demonstrating what their child sees through each eye, and provide age-appropriate information about amblyopia and its treatment.

Beyond the clinic, families will have access to a virtual version of the robot through an online platform, offering ongoing support and motivation.

Dr. Ben Thompson, the project lead from the School of Optometry & Vision Science, explains, "We've seen social robots being used effectively in settings such as restaurants but not in eye care. This project is proof of concept to see if we can use them effectively for patient education."

Dr. Kerstin Dautenhahn from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering adds, "Compared with using a tablet or computer, there is a lot of research that shows children find working with social robots more enjoyable; they want to interact with them."

The team has received funding from the New Frontiers in Research Fund to conduct a two-year study. This research will examine patching adherence and changes in children's vision, observe interactions between children, families, and the robot, and assess psychological well-being over time.

Dr. Maureen Drysdale, a psychology professor at St. Jerome's University, hypothesizes that engaging with the robot will be a positive experience for children, potentially improving their mental health and well-being.

“Research shows that children with amblyopia experience challenges such as reading difficulties, lowered self-esteem and reduced emotional well-being,” said Dr. Maureen Drysdale. “Robots are exciting for kids, so I hypothesize that engaging with one will be a positive experience – and positive experiences have positive mental health and well-being implications. The robot may also improve parents’ well-being by reducing the pressure on them to make their children adhere to the treatment.”

If successful, the researchers believe this approach could be applied to other medical conditions to improve health outcomes. As Dr. Marlee Spafford, a professor emerita of optometry, concludes, "If the social robot helps improve treatment adherence, it will help improve vision, and that will make a difference in a child's life over the long term."