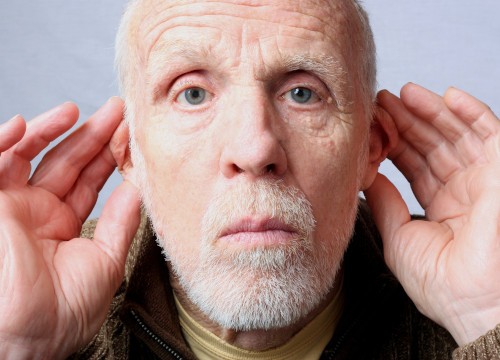

Early Signs of Hearing Loss May Be Detected Through Eye Movements

Hearing loss is a prevalent concern for people as they age, with approximately 40% of individuals experiencing some degree of hearing impairment. While age-related hearing loss is most commonly associated with those over 65, it can manifest earlier, often emerging in people's 40s or 50s. Recognizing the need for early detection, researchers at the Rotman Research Institute in Canada have explored a groundbreaking approach to identifying subtler forms of hearing loss through the observation of eye movements.

Hearing loss is a prevalent concern for people as they age, with approximately 40% of individuals experiencing some degree of hearing impairment. While age-related hearing loss is most commonly associated with those over 65, it can manifest earlier, often emerging in people's 40s or 50s. Recognizing the need for early detection, researchers at the Rotman Research Institute in Canada have explored a groundbreaking approach to identifying subtler forms of hearing loss through the observation of eye movements.

Published in The Journal of Neuroscience, their recent study suggests that eye movements tend to decrease when young adults exert more effort to understand speech, even in challenging environments. This research opens up a promising avenue for diagnosing hearing problems sooner and improving clinical assessments.

Björn Herrmann, co-author of the paper, explained, "We typically diagnose hearing loss using pure-tone audiometry, which involves assessing a person's ability to hear pure tones at different sound levels. If the hearing threshold is too high, indicating the need for intense tones to be heard, hearing aids may be prescribed. However, age-related hearing loss often begins in one's 40s or 50s, and standard audiometry may not capture early signs."

The early stages of hearing loss often manifest as difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments, such as crowded restaurants or shopping malls. These challenges serve as precursors to more severe hearing loss later in life, but traditional audiometric thresholds may not effectively detect these early signs.

To address this gap, researchers have been working to develop additional diagnostic tools that capture the subtler aspects of hearing, including physiological signs that indicate heightened effort during listening. Objective measures of listening effort can provide valuable insights for both new patients and those undergoing hearing loss treatments, helping clinicians better assess and tailor treatment plans.

Herrmann emphasized the significance of objective measures, stating, "Asking a person how effortful they find listening can be subjective and influenced by personal interpretations. Objective measures are seen as advantageous in clinical and research contexts."

Previous studies have identified various physiological responses associated with effortful listening, with one common indicator being changes in pupil size, which can be measured using pupillometry. However, measuring pupil size during hearing tests has limitations, including sensitivity to changes in lighting conditions and pupil angle.

Herrmann and colleague M. Eric Cui sought an alternative strategy by investigating the connection between eye movements and cognitive effort during listening tasks. They hypothesized that reduced eye movements might indicate increased auditory sensitivity to speech and cognitive effort.

The researchers conducted experiments involving 26 young adults, aged 18 to 35, using an eye tracker to monitor their eye movements while they listened to sentences and stories in varying degrees of background noise. The participants' focus ranged from stationary dots to multiple moving dots on a computer screen.

Their analyses focused on two aspects of eye movements: fixation duration (how long the eyes remained fixed on an object) and gaze dispersion (how often the eyes moved across the screen). The results showed that under more effortful listening conditions, characterized by high levels of background noise, participants exhibited longer fixation durations and reduced gaze dispersion.

Herrmann explained the significance of their findings, stating, "Our study and another study published around the same time as ours are the first to show that listening effort is associated with reduced eye movements. This discovery could pave the way for new clinical tests to detect hearing loss."

The researchers acknowledge the need for further investigations to understand the relationship between eye movements and other physiological responses, such as pupil size, and to explore differences in listening effort related to factors beyond hearing loss.

Future studies will delve into the mechanisms behind reduced eye movements and aim to determine whether these findings extend to older adults. Additionally, Herrmann and Cui plan to investigate whether eye movements can indicate reduced listening effort when individuals use hearing aids, potentially assisting in evaluating the effectiveness of hearing aid prescriptions.

Effortful listening, as revealed by this study, holds the promise of serving as an early indicator of hearing loss, offering hope for improved interventions and better hearing health for people of all ages.